by Nicole Sowers based on an original post by Crystal Maertens

Data continues to emerge that support the negative impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, on adult health. Using ACEs scores and the Bridges Out of Poverty framework together can provide a holistic approach that addresses both trauma and socioeconomic barriers to health.

What Are ACEs?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0–17 years), such as experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect; witnessing violence in the home or community; or having a family member attempt or die by suicide.” ACEs also include aspects of a child’s environment that undermine safety or stability — such as substance misuse, mental illness, or instability caused by parental separation or incarceration.

Background: The ACE Study

Between 1995 and 1997, Kaiser Permanente and the CDC surveyed over 17,000 adults in Southern California about childhood trauma. More than half of respondents reported at least one ACE, and one-fourth reported two or more. The study demonstrated a strong graded relationship between ACEs and later health outcomes: those with four or more ACEs were multiple times more likely to experience chronic illnesses, mental health issues, or risky behaviors compared to those with none.

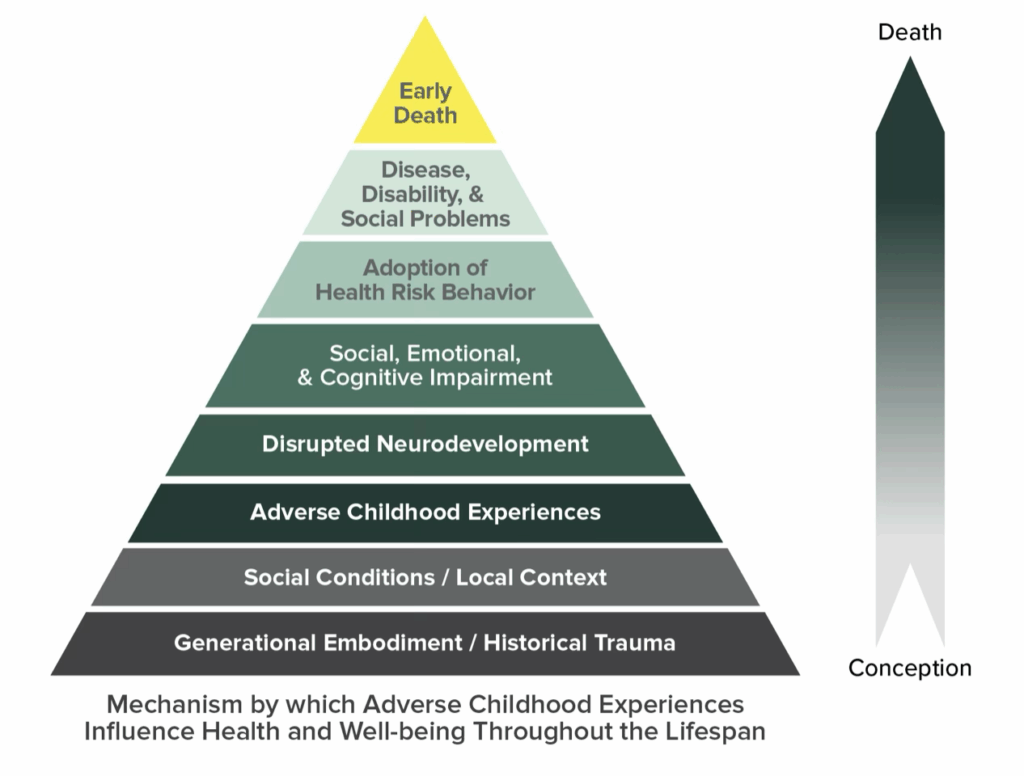

ACE Pyramid

The ACE Pyramid, developed by the CDC, visually demonstrates how ACEs influence lifelong health — from disrupted neurodevelopment to early death.

The ACE Score

An ACE score counts how many types of adverse experiences a person reports. The original study identified 10 key ACE categories: emotional, physical, or sexual abuse; emotional or physical neglect; and household dysfunction such as substance use, mental illness, incarceration, domestic violence, or parental separation. You can take a brief ACE self-assessment to see your score.

What Does the ACE Score Mean?

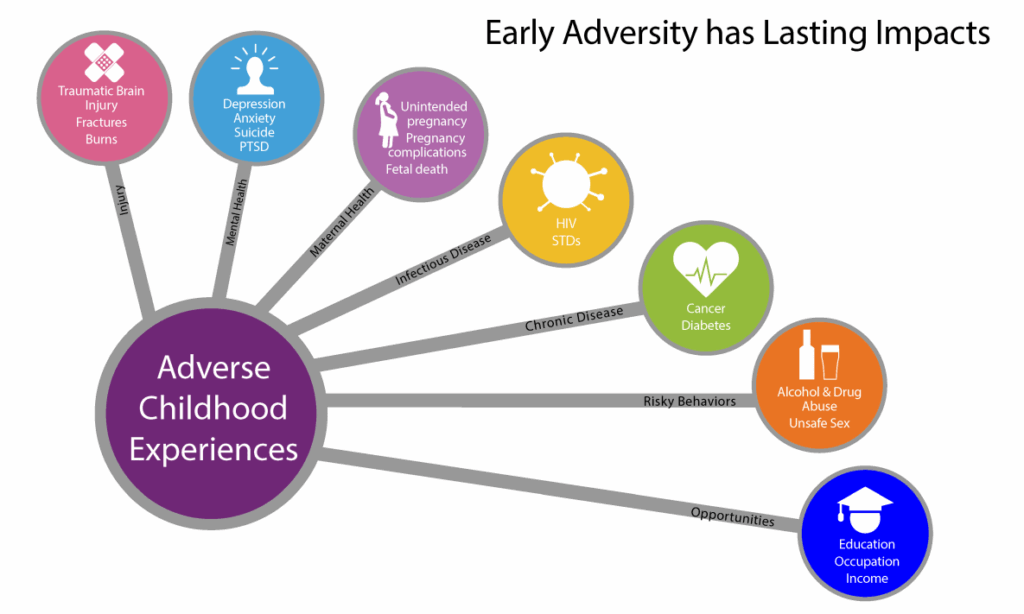

People with higher ACE scores face increased risks of chronic disease, mental health challenges, and unhealthy behaviors. Toxic stress from early trauma disrupts brain development, weakens the immune system, and affects how the body manages stress.

However, ACEs are not destiny. Protective factors — safe relationships, nurturing adults, and stable environments — can buffer the effects of trauma. That protection factor is resiliency.

Resiliency

As defined by the Center for Child Counseling, “Resilience is the ability to bounce back from life’s difficulties. It is a varied and dynamic mix of many traits like determination, toughness, optimism, faith, positivity and hope. Resilience isn’t necessarily something a child is born with, although scientists now believe that certain children are genetically predisposed to higher levels of resilience.

But the good news for all children is that resilience is like a muscle – the more you exercise it, the stronger it grows, especially in very young children where neural pathways are still forming and thinking patterns are elastic.”

How ACEs and Bridges Out of Poverty Work Together

The ACEs framework and the Bridges Out of Poverty model are complementary lenses for improving community well-being. ACEs focus on the biological and emotional impacts of trauma, while Bridges Out of Poverty focuses on social and economic conditions that affect resilience and recovery.

When used together, they provide a holistic approach that addresses both trauma and socioeconomic barriers to health. Source: Champ Software Bridges Blog – https://champsoftware.com/bridges-out-of-poverty/

How ACEs Pair with the Social Determinants of Health to Create a Holistic Picture

The social determinants of health (SDOH) — the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age — profoundly shape health outcomes. Adverse Childhood Experiences and social determinants of health (SDOH) are deeply intertwined. Early trauma often coincides with socioeconomic instability, unsafe environments, food and housing insecurity, and limited access to care. ACEs contribute to, and are worsened by, inequities in education, income, and neighborhood conditions.

Viewing ACEs through the SDOH lens enables public health professionals to address upstream factors like poverty, discrimination, and housing, while also mitigating downstream consequences of trauma such as chronic disease and poor mental health.

Sources: Minnesota Department of Health https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/ace/sdoh.html, AFMC.org – https://www.afmc.org/blog/aces-sdoh, and American Academy of Pediatrics – https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/156/1/e2024069605/202235/The-Intersection-of-Neighborhood-Environments

For more on the intersection of ACEs and SDOH watch episode 94 on AFMC TV from May 17, 2023.

In the next blog, we will discuss how ACEs impact public health and what public health workers can do to prevent, mitigate and document ACEs in ways that help clients and the community.

Tools and Resources for Addressing Community Health Through Trauma-Informed Care